|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A successful illustrator and painter, Kahlil Gibran was

also a prolific writer. Among his novels and collections of poetry are The Madman,

his first book written and published in English (1918), Sand and Foam (1926), and The Wanderer (1932). Over a decade after his death in 1931 at age 48,

several of his earlier works, written in Arabic, were reintroduced in English, including Spirits Rebellious (1948) and A Tear and a Smile (1950).

|

|

If there is a man or If there is a man or

woman who can read

this book without a

|

|

|

THE PROPHET

“COUNSELS”

in the order they appear in the book:

|

|

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

|

|

ON LOVE

ON MARRIAGE

ON CHILDREN

ON GIVING

ON EATING

AND DRINKING

ON WORK

ON JOY

AND SORROW

ON HOUSES

ON CLOTHES

ON BUYING

AND SELLING

ON CRIME

AND PUNISHMENT

ON LAWS

ON FREEDOM

ON REASON

AND PASSION

ON PAIN

ON SELF-KNOWLEDGE

ON TEACHING

ON FRIENDSHIP

ON TALKING

ON TIME

ON GOOD

AND EVIL

ON PRAYER

ON PLEASURE

ON BEAUTY

ON RELIGION

ON DEATH

|

|

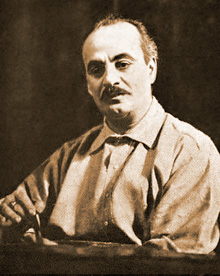

Above: A photo of young Gibran generally credited to avante-garde photographer Fred Holland Day, entitled “Man with a Book.” |

|

|

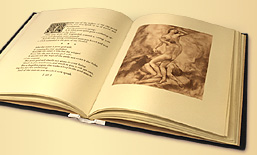

But it was his book, The Prophet, first published in 1926, that cemented his reputation as an author and poet,

while bringing additional recognition for his art. The now classic volume has been translated into more than twenty languages, with successive U.S. editions selling

more than eleven million copies to date.

|

|

SUMMARY

The book’s central storyline revolves around Almustafa, the “chosen and beloved,” whose twelve-year sojourn

in the faraway, long-ago City of Orphalese is about to end. Most of those dozen years have been spent in the hills overlooking Orphalese, where Almustafa has been

witness to the daily triumphs and tragedies in the inhabitants’ lives. When he climbs a hill outside the city walls one day to spy “his ship coming with

the mist” — a ship destined to return him to the isle of his birth — he re-enters the city and goes to the temple to bid farewell.

|

|

The people of Orphalese, who realize with regret what is happening, assemble below the temple steps, reluctant

to let Almustafa leave without passing on what he has learned during his stay. The temple’s seer, Almitra, who believes in his prophetic mission, prompts him to

dispense his accumulated wisdom with the simple query: “Speak to us of Love.”

|

|

Almustafa’s insightful response, delivered in almost scriptural language and with obvious

passion, inspire the people to ask him about other subjects close to their hearts. There are 26 questions-and-responses in all, on topics that span the human condition

from birth to death. (See listing at left.) Almustafa speaks with an understanding and depth which clearly demonstrates that he hasn’t been as aloof from their

lives as some of them thought. And even his most cutting criticisms of their weaknesses and follies reveal a great compassion and love for them.

|

|

quiet acceptance of a

great man’s philosophy

and a singing in the heart

as of music born within,

that (person) is indeed

dead to life and truth.

His power came from His power came from

some great reservoir

of spiritual life else it

could not have been so

universal and so potent,

but the majesty and

beauty of the language

with which he clothed

it were all his own.

Gibran’s purpose was Gibran’s purpose was

a lofty one, and his belief

in the ‘unity of being,’

which led him to call for

universal fellowship and

the unification of the human

race, is a message which

retains its potency today.

|

|

|

Which is why, after bestowing his final counsel on death, Almustafa can hardly

bring himself to board the sailing ship that now awaits him in the harbor. After all, he says, “…Ever has it been that love knows not its own depth

until the hour of separation.” And then, as if to reassure the people that his departure is only temporary, he repeats a line he’d spoken earlier,

telling them that “…a little while, a moment of rest upon the wind, and another woman shall bear me.”

FURTHER REFLECTIONS

That final line, for some reviewers of the book, alludes to Gibran’s personal belief in “the transmigration of souls” — or what

some people think of, simplistically, as “reincarnation.” (The concept was common in the Romantic art and literature of the time, largely

due to a growing fascination with the Eastern philosophies that were just becoming known in the West.) But the line might just as easily allude to

the belief, common in many world religions, that in every age a new Prophet is born, sent to earth by The Divine to speak the words each new generation

most needs to hear.

And it is precisely this philosophical “flexibility” that makes The Prophet’s message so universal. Like the ability of the

world’s sacred writings to speak across the boundaries of time and culture, Gibran’s words embody a core of truth, yet allow room for

interpretation and application to one’s present conditions. Though some scriptural literalists might see The Prophet as competing or

conflicting with their own religious orientation, most readers will see Almustafa’s words as complementary and even supportive of the spiritual

wisdom in their own faith. And for readers who find little consolation or guidance in any of the world’s religious traditions, The Prophet

can be a link to the same deeper Source religions claim to draw upon.

|

|

|

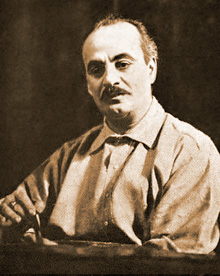

MORE ON GIBRAN’S LIFE

Born in the Maronite Christian village of B’sharri, in what is today Northern Lebanon (then part of the Turkish/Ottoman Empire), Kahlil Gibran

was raised in relative poverty. Gibran — pronounced with a “J” sound rather than a hard “G” — did not receive any formal

schooling; but through his religious education he learned about the Bible, as well as his Syriac and surrounding Arabic culture. It was here in the

hills of Lebanon, Gibran would claim, that the storyline for The Prophet first came to him.

|

|

However, in the aftermath of his father’s legal and financial failings,

Gibran’s mother, younger sisters Mariana and Sultana, and half-brother Peter, left Lebanon for America — first to New York, then to Boston,

in 1895. Kahlil was all of 12 years old.

He was also talented enough that, as soon as be began attending school, his “hobby” of drawing came to the attention of his teachers.

He was promptly introduced to avant-garde artist Fred Holland Day, who encouraged and supported Gibran’s early creative endeavors. Through

Day and his artistic associates, the young Gibran would develop his characteristic style, notably his symbolic, mystical approach to his artwork,

and his fondness for the themes of English Romanticism. At his first art exhibition in Day’s studio in 1904, Gibran met the headmistress of

another Boston school, Mary Haskell, who would soon become his greatest advocate, patron and mentor.

While continuing to study fine art — even going off to Paris with Mary’s

financial help — Gibran began his writing career. His early efforts, in Arabic, focused largely on subjects related to his experiences as an immigrant,

on the emergence of a Syrian/Lebanese/Arab identity independent of the Ottoman occupiers, and on the corruption of the Eastern churches who were often in

collaboration with the Turks. |

|

|

ABOVE: Gibran’s hometown of B’sharri, Lebanon, almost idyllic with its verdant, craggy hillsides, valleys and surrounding mountains. |

|

|

|

|

It was said that the Maronite Church excommunicated Gibran for those writings,

a charge the church later denied. In any case, his dissatisfaction with organized religion and its collaboration with whomever happened to be in power,

probably inspired Gibran’s personal journey toward a “spirituality” independent of religious and political affiliation. His literary works,

which finally began to appear in English (as Mary Haskell continued to tutor him in his adopted language), took on a decidedly spiritual emphasis, his

poetry in particular mirroring the lofty cadences of scripture, his themes more universal than reflective of any single religious tradition.

|

|

|

|

|

AT LEFT: A rare photo of Mary Haskell in 1910, joining a friend for a Sierra Club outing

to Yosemite. Gibran was the most famous of several artists and thespians whose careers she assisted. |

|

|

|

It was this spiritual/philosophical emphasis that eventually culminated in The Prophet. Gibran worked on the manuscript for years, s

ometimes trying out passages in public at author’s receptions in New York, where he’d moved his artist’s studio with Mary’s help in 1912.

Mary’s ongoing correspondence (through hand-written letters carefully preserved at the University of North Carolina) demonstrates that she

also helped Gibran polish his prose as he wrote and rewrote The Prophet. It was her recommendation, as well, that he delete

the “thou”s and “thee”s that peppered early drafts, probably in deference to the King James Bible and the Baha’i

writings he’d recently read. Mary also suggested alternative wording for some of Gibran’s classic lines, not all of which he accepted.

Nor did Gibran accept Mary’s suggestion for the book’s title. While she preferred The Counsels, he insisted on a title that

evoked the role of divine spokeman — a role that often stands in opposition to mainstream religious tradition.

|

|

BELOW: Gibran at the height of his success, and already suffering from the illness that would eventually take his life. |

|

|

|

|

|

Mary’s correspondence reveals, too, that she and Kahlil came close to marriage

at one point in their relationship, despite her being ten years his senior.

Apparently Mary sensed that Gibran’s off-hand proposal came more out of gratitude for the role she’d played in his life than any real marital desires;

and so their close friendship went on in the same Platonic fashion as before, without ever being “consummated.”

While enjoying a few more successes in both the literary and artistic genres — though nothing would ever approach the impact of The Prophet —

Gibran grew increasingly ill. He died in April, 1931, of liver cancer, having bequeathed the contents of his studio to Mary. It was there she found

Gibran’s collection of her 600-plus letters to him, written over the course of 23 years, along with nearly one hundred original drawings and paintings

which she would eventually donate to the Telfair Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia.

|

|

|

|

The September after his death, Mary and Kahlil’s sister, Mariana, fulfilled

Gibran’s wish to be buried in his native Lebanon. Together they purchased the Mar Sarkis Monastery in B’sharri, where Gibran was finally laid

to rest to the accompaniment of much fanfare for “Lebanon’s most famous native son.” The monastery is now a museum, funded and maintained

by The Gibran National Committee, which was set up to administer Gibran’s estate and collect royalties still flowing from his literary works.

Kahlil Gibran remains the most beloved and widely-read Lebanese-American author, and is the best-selling poet of all time after Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu.

Additional biographical information and collections of Gibran’s artwork may be read and viewed at dozens of sites across

the world-wide-web. For some of the major resources, please go to our LINKS page. |

|

|

|

|

|